Colonial Architecture: Georgian, Federal and Revival Styles

Updating Your Colonial House?

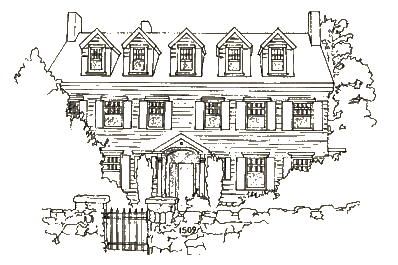

Drawing: Victoria Heritage Foundation.

Drawing: Victoria Heritage Foundation.

We specialize in updating period homes while preserving the feel, style, and craftsmanship of the historic era. Seamlessly incorporate a modern kitchen, bath or addition into your Colonial home.

Colonial styles developed in England between 1720 and 1840 and were imported into the then English Colonies in America by English Settlers. The kings of England during this period were the four "German Georges" of the House of Hanover who collectively reigned from 1714 to 1830, so the architecture that emerged during their reigns became known as the "Georgian" style.

Georgian architecture style was intended to reflect Renaissance ideals made popular by Sir Christopher Wren, Britain's most famous architect of the 17th century. It was a simplification of earlier, more ornate Baroque styles. Typically rectangular and symmetrical, two rooms deep and two stories high (Four over Four) with one or more chimneys extending through the roof or at either end.

Brick or clapboard with the rarer shingle siding are the usual exterior finishes. The classic double-hung window was first widely used with this style. English Georgian featured hip roofs while in North America the gable-end roof was more common.

High-style Georgian homes often contained an oval or round parlor, the most famous of which is the Oval Office in the White House — originally intended as a sitting room or parlor. The White House is a Georgian design. (For more information on the builder of the White House, see Building by Design: he Design-Build Concept.)

The Georgian variation known as the "Federal-style" was developed in Scotland by architect Robert Adam. In England, it is known as the "Adamesque" form of the Georgian style. In the former colonies, it was named the "Federal" style by Americans eager to divorce themselves from everything British after the American Revolution.

Its main identifying feature of the style is an elaborate entryway with classical detailing and commonly an arch-top or Palladian window at the center of the second story.

The main entry door is usually centered on the front facade with a semi-circular or elliptical fanlight window above it and often flanked by leaded glass sidelights. The door is typically framed with simple pilasters and a broken triangular pediment. The entry pediment was often extended to create a porch which may be rectangular or elliptical and is often supported by groupings of slender, simple Doric columns.

The use of classical elements such as columns and arches is typical of the Federal period. The front facade is symmetrical. The area to the right of the entry was a mirror image of the area to the left. This rigid symmetry is one of the distinguishing characteristics of Georgian houses in general and Federal architecture in particular.

A number of variations of the Georgian house developed in the Colonies. The Cape Cod is a single story version of the Georgian house as is the Saltbox house.

The Saltbox never gained wide acceptance outside of New England but the Cape Cod-style swept the country several times and can be found from coast to coast and at all points in between.

It is boxy and low to the ground with a sharply pitched roof and narrow eaves. The style reappeared several times in American architectural history. It briefly emerged again from the shadow of ever-more-elaborate Victorian architecture in the late 19th century Colonial Revival period, then again beginning in the 1920s when it was re-popularized once more by Boston architect Royal Barry Wills whose writings sparked a revival of early Colonial styles, primarily in New England.

In the housing boom that followed the Second World War, the style was resurrected once again by the Levitt brothers who adopted the Cape Cod to their mass production building techniques in their various Levittowns; and both the style and the techniques were adopted widely across the country.

Nebraska's classic colonial homes were built in the late 19th century during the Colonial Revival movement that began about 1870. It was given considerable momentum by the 1876 Centennial Exhibition which reawakened Americans to their colonial heritage. It was largely a stylistic backlash against the excesses of ever-more-elaborate Victorian housing styles and a yearning to return to the country's "more wholesome" agrarian past. This sentiment helped trigger the Arts and Crafts movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that gave rise to a family of architectural styles that paralleled the Colonial Revival until the start of World War II.

The movement spun off a variety of sub-types, including the Dutch Colonial style identified by its gambrel roof.

In the Colonial Era, wood trim was made by hand. The process was labor-intensive and time-consuming. Decoration was expensive and used sparingly. By contrast, Revival houses were often richly embellished with highly decorated facades and elaborate pediments using inexpensive molding and trim mass-produced in factories.

There were also structural differences. Ceilings in Colonial times tended to be low — 7' to 7'6" was typical. Lower ceilings used fewer materials and were easier to heat. Walls were covered in wood strips, and woodwork was more often painted than stained. By the 1870s dimension lumber from steam-powered mills was abundant and readily available. Ceilings were raised to as high as 10 feet on the main floor, the now-standard 8 feet everywhere else.

The Colonial styles were re-popularized one again as part of the housing boom that followed the end of World War II. However, the "Colonial" styles common in Postwar housing were only a very distant descendant of the original Georgian architecture. Split foyer and split-level colonials were stripped of most Georgian style elements and incorporate many features of the modern Ranch style house. See Postwar Styles: Cape Cod, Colonial, and Ranch for more information on Postwar styles.

Colonial Interiors

You would not want to live in an actual colonial house. With no kitchen, no bathrooms, and no closets (See Beyond the Closet — 21st Century Storage Solutions) life would be a little more challenging than we are used to today.

While we know what a colonial parlor probably looked like since parlors are represented in many period drawings and woodcuts, the "colonial" kitchen and bath are modern interpretations. The actually colonial bath was a tin tub in front of the fireplace. So, since there were no kitchens or baths as we know them today, we have to imagine what the rooms might have looked like if our Founding Fathers had owned toilets, microwaves, and dishwashers. American colonial style blends English Georgian elements with American informality for a more relaxed atmosphere than the stilted English parlor.

Interior decoration was spare in Colonial times and relied primarily on paint for color and plaster for texture. Wood-paneled walls, wide moldings, woven floor coverings, wing chairs, Chippendale and Queen Anne furnishings, damask fabrics and elaborate draperies (needed to keep out drafts) are the hallmarks of the Colonial interior style. A grandfather clock fits in very well.

Moldings are usually wide, deep and painted. Painted moldings are common. Wood stain did not come into wide use until the Colonial Revival of the late 19th century when ready-mixed wood stains from paint companies such as Pratt & Lambert became available. Earlier stains were made on-site by skilled craftsmen using techniques barely changed since the Roman Empire. Iron nails soaked in vinegar rendered a dark gray or ebony stain. Brown stain was created by soaking tobacco in ammonia and water. None of these was very durable and faded rapidly in direct sunlight.

Gypsum plaster replaced by lime plaster in the 1800s. It cured in days rather than months making it a much more practical material. Lath and plaster walls replaced wood boards as the preferred wall covering during the Revival period.

Ceiling beams would not be out of place. Door and window trim was originally simple with flat or gently curved moldings suitable for hand shaping. After steam lumber mills made moldings much less expensive and widely available, more elaborate moldings became more popular in Colonial interiors and are found in abundance in Revival Colonials.

Windows were trimmed with a stool (inside sill) and apron. Floors in the 19th century were usually wide plank pine, often 1 1/2" to 2" thick laid without a subfloor and typically unfinished except for the occasional coat of wax.

By the Colonial Revival floors were oak in parlors and "public" rooms; strip pine in family and utility rooms. Mill-produced floorboards, unlike the hand-sawn boards of the Colonial period, were tongued and grooved which allowed them to be installed with hidden cut nails.

Finish flooring was laid over a subfloor often with oil- or asphalt-impregnated paper sandwiched between the finish floor and subfloor as an air barrier to keep out drafts. Late in the Revival period floors began to be shellacked then varnished and regularly waxed to maintain their shine and protect the finish.

Stone was common in entries, kitchens, and baths. Ceramic tile as we know it today was very rare in the colonial period. The little that was available had to be imported from Europe and was very expensive. But the much less expensive and readily available tile from domestic kilns was used rather lavishly in Colonial Revival houses of the late 19th century.

The Colonial Kitchen

The kitchen style most compatible with this architecture is, naturally, a Colonial or Traditional style. This style includes a wide range of features and finishes and is very adaptable to your personal tastes.

Cabinets

Colonial cabinets typically feature raised panels intermixed with glass small-lite doors, either curved or flat top, in cherry, hickory, maple, oak, or painted wood. A more exotic domestic wood, such as birch or chestnut, is also a good choice. Imported woods are not. Beaded door styles also work well. Door styles and finishes can be mixed and matched for special effects.

It is very common to see painted and stained cabinets in the same kitchen. The paint in Colonial times would have been milk paint. Enamel and other ready-mix paints were not introduced until the middle of the 19th century. The factory-produced paints are much more durable and washable and require less maintenance but milk paint has an unmistakable luster that is not available in oil-based or latex paints.

Tall wall cabinets should go all the way to the ceiling in at least a few spots. Soffits, if any, should be shallow. Feet on cabinets rather than recessed toe kicks make the cabinets look less "built-in" and more like the furniture common in Colonial Revival kitchens. For more information see "Cabinet Basics"> For more examples of colonial cabinet door styles, see Cabinet Door Styles.

Countertops

The classic Colonial countertop is soapstone but granite and laminate (especially laminate that looks like granite or soapstone) also work well. Tile countertops became more common during the Colonial Revival but were still fairly unusual. (For more information see "New and Traditional Countertop Choices".)

Other materials of the Victorian Colonial Revival period including wood, zinc, and enameled porcelain are appropriate. Marble is sometimes seen in butler's pantries in Revival homes but we have never seen it used in the kitchen proper. Soft, easily stained and vulnerable to damage by even mild acids like lemon juice and vinegar, it would probably not be a good material for kitchen countertops. For more information see The Victorian Styles: Queen Anne, Italianate, Gothic Revival, and Eastlake.

Flooring

For kitchen flooring, wide plank pine finished in a matte polyurethane to simulate an unfinished floor is the first choice. The Colonial revival of the 19th century introduced newer flooring options: true linoleum, strip oak, and cork being the most common.

Most Requested Feature

Ceramic and stone are also good choices. The look of wide plank wood using modern laminate or ceramic tile flooring is an option but would not be our first choice. For more information see "Flooring Options for Kitchens and Baths.")

The most requested feature in a Colonial Kitchen is a working fireplace. In early American homes, the fireplace was not only the main heat source in the house but also the cookstove. The huge open wood-burning hearths of yesteryear are out of place in modern homes but nothing produces a feeling of coziness like a working fireplace. Today's natural gas or LP units are safe, efficient and can be remote controlled. Designed just to warm up the kitchen, these units are usually more compact than living room or great room fireplaces and may be vented through the wall rather than up through the roof using an expensive multi-story stove pipe.

Victorian Architectural Styles

Victorian house styles flourished in post-Civil War 19th century American. The trend throughout the later part of the 19th century was toward more ornate homes showcasing the increasing wealth produced by the Industrial Revolution. Mass production processes had made even very elaborate ornamentation relatively inexpensive, and the expansion of… (Continues…).

Rev. 08/09/19